Ruskin’s Analysis of the Nature of Gothic

As a young architectural student, I’d bought into the idea Andrew Hill writes in his book “Ruskinland” and how Ruskin, in order to see the world almost always needed to draw it. But in this belief of Ruskin’s there was always the sense that if you couldn’t draw, then you would never see this “world”. But this is clearly not true if you think of Richard Roger’s inability to draw. In fact, a friend of mine, Michael Hook, was at the AA with Richard Rogers and helped draw up his thesis. If Rogers couldn’t draw, he could certainly see and quite remarkedly so.

He dismissed many of the teachers at my prep school as twerps…

I was very lucky, not unlike Rogers, in that I was quite dyslexic when I was a kid. In those days (1945 onwards) you were simply dismissed as being stupid. Now this suited me down to the ground as it gave me considerable time to draw – not brilliantly, but I drew all the time and supported by my father’s enthusiasm for painting himself, from his days “hob-nobbing” as a fellow Yorkshireman from Bradford with the Dale’s artists like Fred Lawson and his colleagues. He dismissed many of the teachers at my prep school as twerps, but found one who was both interested to help me with my reading with dyslexia and to encourage my drawing as well.

I could certainly draw better than the other kids at the school but so what? But my Dad had the most wonderful of libraries which I longed to explore I promised myself when I had conquered the simple case of reading the word THE! which seems so easy looking back but was hard at the time. In many ways I blame the teachers I had for that, bar one of them, as I frequently had to stand in front of the class! But I was always a bit of a show off, which helped, and got the class laughing. “I see my drawings not merely as descriptive of a particular scene but something more analytical…”

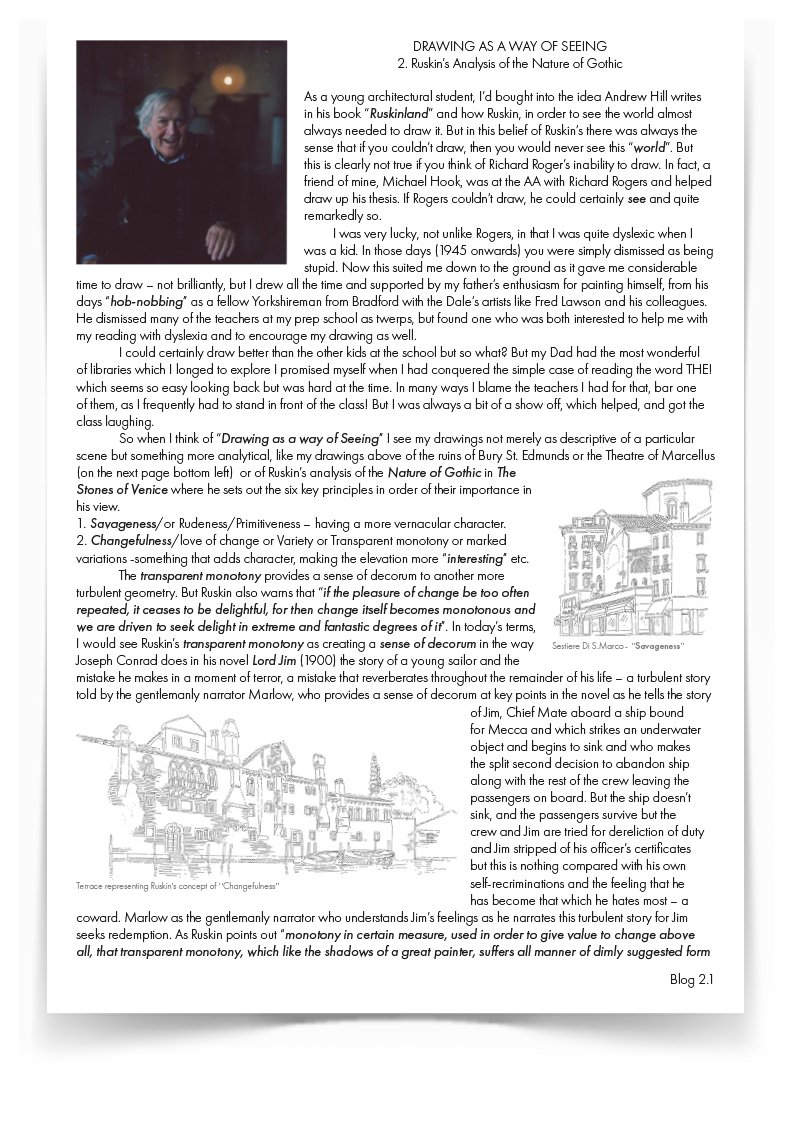

So when I think of “Drawing as a way of Seeing” I see my drawings not merely as descriptive of a particular scene but something more analytical, like my drawings above of the ruins of Bury St. Edmunds or the Theatre of Marcellus or of Ruskin’s analysis of the Nature of Gothic in The Stones of Venice where he sets out the six key principles in order of their importance in his view.

1. Savageness/or Rudeness/Primitiveness – having a more vernacular character.

2. Changefulness/love of change or Variety or Transparent monotony or marked variations -something that adds character, making the elevation more “interesting” etc.

The transparent monotony provides a sense of decorum to another more turbulent geometry. But Ruskin also warns that “if the pleasure of change be too often repeated, it ceases to be delightful, for then change itself becomes monotonous and we are driven to seek delight in extreme and fantastic degrees of it”. In today’s terms, I would see Ruskin’s transparent monotony as creating a sense of decorum in the way Joseph Conrad does in his novel Lord Jim (1900) the story of a young sailor and the mistake he makes in a moment of terror, a mistake that reverberates throughout the remainder of his life – a turbulent story told by the gentlemanly narrator Marlow, who provides a sense of decorum at key points in the novel as he tells the story of Jim, Chief Mate aboard a ship bound for Mecca and which strikes an underwater object and begins to sink and who makes the split second decision to abandon ship along with the rest of the crew leaving the passengers on board. But the ship doesn’t sink, and the passengers survive but the crew and Jim are tried for dereliction of duty and Jim stripped of his officer’s certificates but this is nothing compared with his own self-recriminations and the feeling that he has become that which he hates most – a coward. Marlow as the gentlemanly narrator who understands Jim’s feelings as he narrates this turbulent story for Jim seeks redemption. As Ruskin points out “monotony in certain measure, used in order to give value to change above all, that transparent monotony, which like the shadows of a great painter, suffers all manner of dimly suggested form to be seen through the body of it, is an essential in architectural as in all compositions; and the experience of monotony has about the same place in a healthy mind that the endurance of darkness has”.

Click to view all blog images at larger size.

Ruskin’s third element of the nature of Gothic is 3. Naturalism; that is to say the love of natural objects for their own sake and the effort to represent them frankly, unconstrained by artistic laws - what comes more naturally than the vernacular tradition.

The remaining three points of Ruskin’s characteristic or moral elements of the Gothic, but lower down in his order of importance were: 4. Grotesqueness (or disturbed imagination), 5. Rigidity (obstinacy), 6. Redundance (Generosity).

“We need to think of urban design in terms of reciprocity.”

The problem for the architect today are the last three characteristics or moral elements of Gothic which should be updated and replaced with something more appropriate for our times such as Accretions, Support Structures and Civility in the sense that civility begats civility in the way a punch in the mouth gets you a punch in the mouth back! We need to think of urban design in terms of reciprocity in an architectural way.

In the late 1970’s I had the opportunity as the Director of an EEC funded project “Learning from Vernacular Building and Planning” to explore many of these ideas with a team each year (1978-1988) made up of students from the Universities of Stuttgart and Venice; University College, Dublin and the Polytechnic of the South Bank, where I was a Senior Lecturer. And one of the first study trips we took was to look at the concept of Ruskinian Changefulness in Venice itself (see drawings on Blog 2.2) and I began to see Ruskinian Changefulness as somehow linked to Habrakans’s theory of support structures as we got our sketch books out in the streets and squares of Burano and Mazzorbo, where Giancarlo de Carlo had created a wonderful housing project with Professor Daniele Pini, an old friend of mine, (1979-1985). And this project with its wonderful “humanism” was a great example of the Ruskin thinking in contemporary Venice. It was also a project of De Carlo’s that Richard MacCormac admired so much, and one in which Ruskin’s concept of Savageness and Changefulness are clearly present.

“He was a critic not an architect.”

We set out to examine all this in our study as part of Ruskinian Changefulness out of which grew our theory of accretions – to “accrete by growing” and which was very dependent upon Habrakan’s Support structures (see drawings) concepts that could only be uncovered by the “act of drawing” We set out to examine all this in our study as part of Ruskinian Changefulness out of which grew our theory of accretions – to “accrete by growing” and which was very dependent upon Habrakan’s Support structures (see drawings) concepts that could only be uncovered by the “act of drawing” and in this sense I mean a way of drawing that can take apart the building or buildings under examination in a “forensic way”. Except for his wonderful drawings of the mountains and “the wall veil” Ruskin didn’t venture very much further in his drawings. He was a critic not an architect. It took the talents of Ashbee in his terrace of houses in Cheyne Walk (1897) to show a way of rendering the concept of Ruskinian changefulness. As Alan Crawford points out so well when he refers to the deliberate variety of Ashbee’s design. “Incidents in the streetscape : roof lines shifted from parapet to gable to eaves, and from high to low, the elevations from flat to modelled, regular to irregular” (See RR drawings). Peter Davey, who with Jim Richards was one of two great Editors of The Architectural Review wrote that “When architecture is dominated by object buildings and urbanism by traffic engineers, Townscape’s humanism and respect for context deserves re-appraisal”. And who better to start with than Ashbee who lived his last twenty years in Sevenoaks (not far from where I live) and inspired by Peter Davey, fellow north countryman whose book “Architecture of the Arts and Crafts Movement” (1990) is a treasured possession.

In these days I would take the odd weekend off to meet up with a couple of my teaching friends from Stuttgart - Professor Dieter Houser and Professor Peter Faller of Schroder and Faller. Peter I had taught with since we were both visiting professors at the University of Virginia in 1975 and Dieter and I had met at a conference in Aachen and then taught at Stuttgart. We usually met up in some convienient place I could fly to - I remember going to see my first buildings by Gunther Behnisch, it was his earlier buildings - the Hymnus-Chor-Schule in Stuttgart (1969-70) and his wonderful housing for the Elderly, in Reutlingen Stuttgart (1973-1967), one of the most sensitive of housing schemes I had ever seen up till then. And, as a surpirse my companions took me to see the Schnitz housing at Biberach by Hugo Häring (1950). Sometime before I began teaching with Peter Blundell Jones (1949-2016), when he was teaching at the University of Cambridge, and later at South Bank University. A running joke was ‘‘Who had seen the work of Behnisch first?’’- he or me? He was great fun to be with, a marvelous critic and a brilliant teacher. When I got back to London, I called Peter Davey and went round to the AR to show him what I had seen that weekend. I can justifiably claim that we were the first to publish a building by Behnisch, in an English Architectural Magazine and I would argue that over the years - particularly when we discovered that we had both been short-listed for the Design of the Civic Offices at Epping Forest - there was a lot of laughter and more than a few drinks over the years, especially when he did a teaching stint at the Polytechnic of the South Bank and we would sit on crits together! I learnt a lot from him, and enjoyed his lectures and articles enormously.