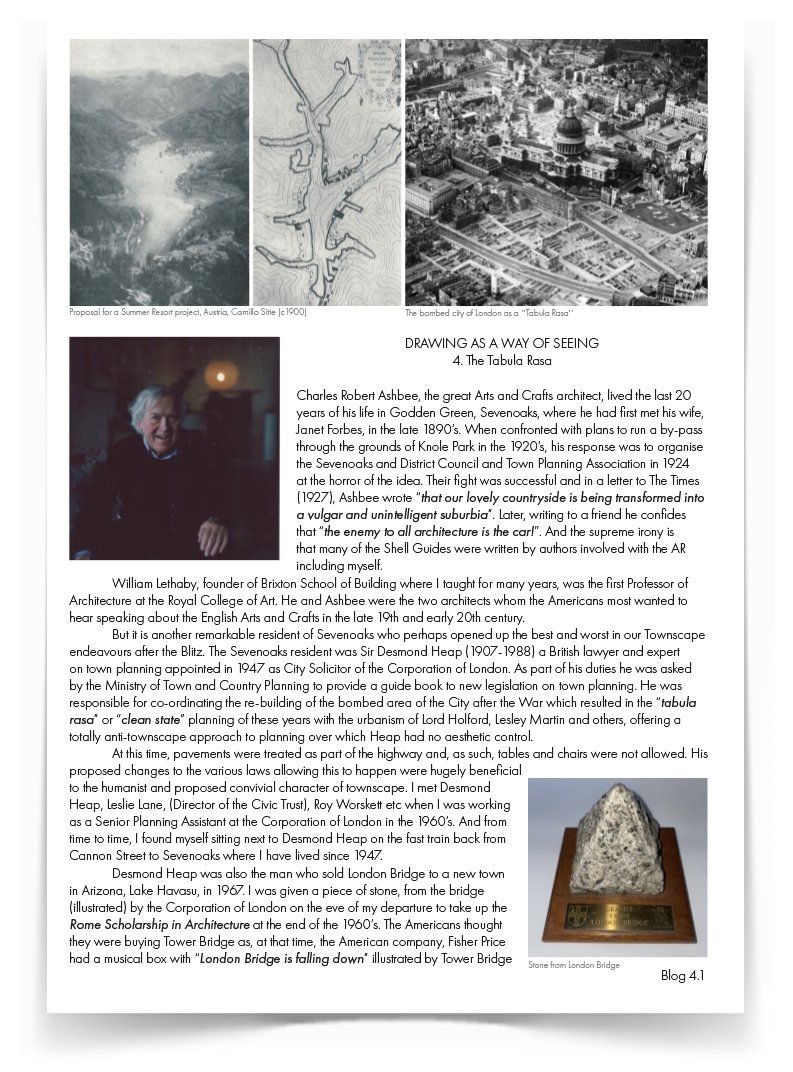

The bombed city of London as a ‘‘Tabula Rasa’’

The Tabula Rasa

Charles Robert Ashbee, the great Arts and Crafts architect, lived the last 20 years of his life in Godden Green, Sevenoaks, where he had first met his wife, Janet Forbes, in the late 1890’s. When confronted with plans to run a by-pass through the grounds of Knole Park in the 1920’s, his response was to organise the Sevenoaks and District Council and Town Planning Association in 1924 at the horror of the idea. Their fight was successful and in a letter to The Times (1927), Ashbee wrote “that our lovely countryside is being transformed into a vulgar and unintelligent suburbia”. Later, writing to a friend he confides that “the enemy to all architecture is the car!”. And the supreme irony is that many of the Shell Guides were written by authors involved with the AR including myself.

William Lethaby, founder of Brixton School of Building where I taught for many years, was the first Professor of Architecture at the Royal College of Art. He and Ashbee were the two architects whom the Americans most wanted to hear speaking about the English Arts and Crafts in the late 19th and early 20th century.

But it is another remarkable resident of Sevenoaks who perhaps opened up the best and worst in our Townscape endeavours after the Blitz. The Sevenoaks resident was Sir Desmond Heap (1907-1988) a British lawyer and expert on town planning appointed in 1947 as City Solicitor of the Corporation of London. As part of his duties he was asked by the Ministry of Town and Country Planning to provide a guide book to new legislation on town planning. He was responsible for co-ordinating the re-building of the bombed area of the City after the War which resulted in the “tabula rasa” or “clean state” planning of these years with the urbanism of Lord Holford, Lesley Martin and others, offering a totally anti-townscape approach to planning over which Heap had no aesthetic control.

At this time, pavements were treated as part of the highway and, as such, tables and chairs were not allowed. His proposed changes to the various laws allowing this to happen were hugely beneficial to the humanist and proposed convivial character of townscape. I met Desmond Heap, Leslie Lane, (Director of the Civic Trust), Roy Worskett etc when I was working as a Senior Planning Assistant at the Corporation of London in the 1960’s. And from time to time, I found myself sitting next to Desmond Heap on the fast train back from Cannon Street to Sevenoaks where I have lived since 1947.

Stone from London Bridge

Desmond Heap was also the man who sold London Bridge to a new town in Arizona, Lake Havasu, in 1967. I was given a piece of stone, from the bridge (illustrated) by the Corporation of London on the eve of my departure to take up the Rome Scholarship in Architecture at the end of the 1960’s. The Americans thought they were buying Tower Bridge as, at that time, the American company, Fisher Price had a musical box with “London Bridge is falling down” illustrated by Tower Bridge on the front of the box. I know this because we had bought our youngest daughter this musical box some years later, when we were in New York.

Sir Gerald Barry (1898-1968) was a long time newspaper editor and was editor of the News Chronicle (1936-1947) when my father became the Features Editor and, in 1948, Barry was appointed Director General of the Festival of Britain (1951). A newspaper editor with “left-leaning middle brow views”, he was energetic and opportunistic with an eye for what would be popular and had a knack of how to motivate others. It was he who wanted Hugh Casson (1910-1999) to be the Director of Architecture for the Festival of Britain, an inspired choice.

Casson had studied architecture at Cambridge (1929-1932) and at the Bartlett School of Architecture (1933-1934). During the war he was a prolific journalist, regularly published in The Architects Journal and The Architectural Review and was a part of the Casson Condor Partnership. He was employed by the camouflage service of the Air Ministry as a designer and later designed the overall site plan for the South Bank exhibition as well as co-ordinating the architects and artists who worked on the project. He was knighted in 1952 for his achievements at the Festival of Britain. He designed stage sets for theatre and opera productions and was responsible for the interior design of the Royal Yacht Britannia etc. He was Professor at the Royal College of Art 1953-1975 and in 1976 he was elected President of the Royal Academy of Arts.

This was the time when I began to produce a regular Townscape column for the motoring magazine Ford Times thanks to all the encouragement of Reyner Banham (who was himself contributing a monthly article on design). And it was during this time that Sir Hugh Casson asked me to come and run a drawing class taking over from Paul Hogarth, my friend, who had a big book assignment at the time but I was a lousy teacher. I had to work hard to get better! However, I was also employed as a planner at the Corporation of London at the time. But Hugh Casson and Nikolas Pevsner both very kindly offered to be referees for me when I applied for the Rome Scholarship in Architecture in 1968. Strangely I began to see more of Nikolas Pevsner at the University of Virginia when I was teaching there in the 1970’s. He came out to Virginia to receive the AIA Gold Medal for his work on the Buildings of England etc.

The City, seen as a Garden of Ideas, Peter Cook, The Monacelli Press, 2003

Will Alsopp’s Bradford Lake Project 2003

The proposed plan designed by Hugh Casson for the Festival of Britain was an inspired design – and an example of Townscape at its more imaginative creating the “City as a Landscape”. It is very interesting when you turn to Peter Cook’s design of the city, seen as a Garden of Ideas (1984) published by The Monacelli Press (2003) and Will Alsop’s Bradford Lakes Project of 2003 which develops similar themes. It is very interesting to see how the contemporary modernism of the 1950’s stands so well alongside the later work of Peter Cook and Will Alsop. This was inspired work from all three.

Even stranger is the potential link to the landscaping of Camillo Sitte in his (c. 1900) proposal for a summer resort project around a reservoir in Upper Austria. If one didn’t know better you could be forgiven for saying that the Sitte-esque proposal in Austria, a project he was said to have been especially fond of had influenced Casson, then Cook, then Alsop. The similarity in the concepts over 103 years is quite remarkable, but I think my connection of all three is just an accident!

Proposal for a Summer Resort project, Austria, Camillo Sitte (c1900)

… that year my first drawings for the Architectural Review were published

It’s the mid 1960’s, I’m 20 years old working with David Rock, when I get a letter from Reyner Banham who had seen some work of mine in a student exhibition, and asked me to come and show my drawings to some of the editors on the Architectural Review. Ian Nairn was especially interested to see my work, and that year my first drawings for the Architectural Review were published. Needless to say, I was not happy with my drawings! But I was certain I could do better.

Ian Nairn, December, Special Enquiry 1956

Oh and one thing I forgot when I was at boarding school there was no TV to watch (or that you were allowed to watch). But when I first saw their book on ‘‘Ian Nairn: Words in Place (1213) Five Leaves Publication’’, I called Gillian Darley, who co-authored this book with David McKie that I had just seen a photo of Ian on my dad’s TV programme, ‘‘Special Enquiry’’ of 1956. Both Ian and my Dad knew Maurice Ashley, the Editor of the Listener, ‘‘a proud Manchester man’’, who commissioned Ian to write a series on ‘‘Britain’s Changing Towns’’. I heard all this at first hand as I would join my Dad and Maurice occasionally for lunch at the Reform Club, where both were members.

‘‘Room by the Sea’’ 1951, Edward Hopper

When the Reform Club finally decided to admit ladies as members in 1980 (long overdue, but the first club to do so) I had taken my wife Thalia, plus my oldest school friend’s wife and Gillian for lunch on that very first day, a great memory of a wonderful lunch! But Gillian and I had lunch at the Reform Club, after publication of their book, and there were things I knew about Ian that she didn’t know (i.e. Ian’s connection with my Dad), and things she knew, but I didn’t. I said that I thought Ian’s photos told you more about many scenes - the skewed tables and chairs in Ian’s photos of Parisian Parks (Nairn’s Paris), and which I had always compared with the Edward Hopper painting of the Sun washed Room, with the open window and the sense of the presence of people. About that time my father had given me a book by the American painter, Robert Henri (1865 - 1929), called The Art Spirit, the leader of the American Ashcan School and great teacher who taught Man Ray and Edward Hopper amongst many others. The book was packed with his teacher’s spirit. Of how ‘‘Beauty is an intangible thing; and cannot be fixed on the surface, and the wear and tear of old age on the body cannot defeat it. Nor will a ‘‘pretty’’ face make it for ‘‘pretty faces are often dull and empty, and beauty is never dull and it fits all spaces’’. (1923) Ian Nairn and Robert Henri were remarkably alike in their enthusiasms for the often-forgotten sections of cities. You begin to see this when you read Ian’s book, ‘‘The American Landscape: A Critical View’’ (1965) Random House.

My Egypt, Charles Demuth, (1927)

Sighted in Banham’s A Concrete Atlantis, 1986

In Section 4 IDENTITY, Ian writes of ‘‘the agents of the nobility were the grain elevators; and though not every town in America possesses such unconscious masterpieces.’’ It brought Ian closer to his fellow AR editor Reyner Banham in ‘‘A Concrete Atlantis’’ (1986) and of those in Buffalo being an ‘‘inspiration to modern architecture in Europe’’ as was Charles Demuth’s (a contemporary of Robert Henri) in his painting My Egypt (1927) with the grain elevators representing American’s sense of loss of antiquity and though not every town in America possesses such unconcious masterpieces’’. It brought Ian Nairn closer to Reyner Banham, particularly since Ian was writing about this in 1965 and Reyner Banham not until the book ‘‘A Concrete Atlantis’’ was published in 1986 by MIT. For many architects, who were only familiar with the latter Banham book were hooked, particularly so, I believe because the examples cited in Buffalo by Banham were ‘‘an inspiration to modern architecture in Europe’’ (all be it 22 years after Ian Nairn had discussed them).

Banham goes onto write ‘‘these beautiful forms, the most beautiful forms’’, praised by Le Corbusier ‘‘ pure and uncluttered, but black against the green of the summer grass and scrub’’ Walter Gropius, Banham points out, had a belief that ‘‘American engineers had retained some aboriginalism’ and that their work was therefore comparable to that surviving from Ancient Egypt’’.

The American Landscape, Ian Nairn, 1965 - ‘‘These take over, play the sublime game, black against white, cylindrical against angular,until the big silos seem to overpower the whole view’’.

But Nairn (who many believed had very opposed views to those of Banham, had already been singing the praises of such industrial monuments in his 1964 book on The American Landscape and yet neither appear to mention the importance artistically of all of this in the work of Charles Demuth, as Barbara Rose points out in ‘‘American Art Since 1910: A Critical History/Praegar (1967) p.12’’ Sometimes drove artists like Demuth to make symbolic comparisons though he was able to discover monumentality in the grain forms of grain elevators Demuth expressed this sense of loss by comparing the grain elevators with the pyraminds of antiquity, ironically titling them ‘‘My Egypt (1927)’’.